Ian Dejardin, the Sackler Director of Dulwich Picture Gallery introduces the Gallery’s spring exhibition ‘Hockney Printmaker’. 5 February – 11 May 2014.

“This exhibition reminds us that, alongside that dazzling career as Britain’s favourite painter, Hockney’s parallel achievement as a printmaker deserves equal celebration for its longevity (it’s 60 years since that first print), variety and technical brilliance, not to mention its wit and sophistication”

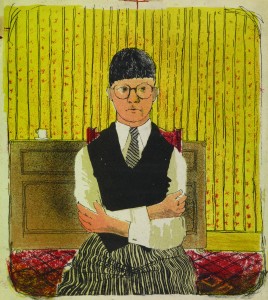

David Hockney, Self Portrait, 1954, Lithograph in Five Colors, 11 1/2 x 10 1/4″ Edition: 5 (approximately) © David Hockney

A year or two ago, I experienced one of those rare moments of revelation, when you suddenly pick up an insight into something you saw for the first time, in this case, over forty years ago. I was at an exhibition featuring Giorgio Morandi’s etchings, which are things of endlessly subtle beauty, of course. A very distinctive feature of his etchings is his use of a kind of cross-hatching, in emulation of Victorian mechanical etching processes designed to achieve prodigious degrees of shading without causing the etcher’s hand to fall off in agony, but used by Morandi absolutely differently in flat, softly-textured planes purely for their visual effect. The revelation? I suddenly realised what David Hockney must have been looking at to achieve some of the effects in his magical illustrations to Grimm’s Fairy Tales, first published in 1970, a series of prints that made the greatest possible impact on me as a teenager. Hockney was of course already famous for paintings like A Bigger Splash (1967, Tate), and for his meticulously crafted image – blonde hair, big dark-rimmed spectacles, and uniquely inspiring fashion sense - but until my sister acquired that little book of Fairy Tales, I had been unaware of Hockney’s prowess as a printmaker and storyteller.

“His earliest print, the wonderful Self-portrait of 1954, in which he embodied his then adulation of Stanley Spencer by copying that famous eccentric’s pudding-bowl haircut, pre-bleach, was done when still in Bradford.”

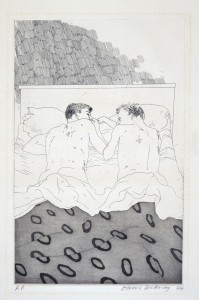

David Hockney, Two Boys Aged 23 or 24 from Illustrations For Fourteen Poems from C.P. Cavafy, 1966-67, Etching, 31 1/2 x 22

In fact, these images were startling on many levels. They revealed an artist who made witty and wide-ranging reference to other artists and media – witness the cinematic bogeyman looming fruitlessly behind the resolutely unterrified figure of the ‘boy who left home to learn fear’ (Inside the Castle); or the anti-Madonna of The Enchantress with the Baby Rapunzel, which combines references to Hieronymous Bosch’s The Virgin and Child and the Three Magi with the trees from the background of Leonardo’s Annunciation. And the Morandi moment?: most beautifully in The Pot Boiling, the image of the pot of water, just beginning to bubble, into which the cook plans to throw Fundevogel.

Other images left an indelible impression through their sheer imaginative beauty – the boy hidden in a fish from The Little Sea Hare, or the same boy hidden magically within an egg: obviously one should not be able to see the boy at all in his hiding places, but Hockney deals with the anomaly technically – the boy is drawn in outline only, with no shading, so that at first all one sees is the fish and the egg, but as you get closer, the figure within becomes apparent. It’s marvellously effective, and utterly simple.

“At the time, showing homosexual relationships in this straightforward and touching manner was still unheard of, and Hockney’s powerful role in breaking down some of those barriers through these poetic prints was extremely important.”

This technical approach to the creation of visual magic turns out to be more than simply a visual trick. In fact, Hockney was experimenting with different types of etching – soft and hard ground, for instance – to achieve different effects within the same print. Soft-ground allows the artist to draw on paper laid on top of the grounded plate, which is prepared with a softer form of wax which thus reproduces the act of drawing. Hard ground uses a harder wax – and in fact produces a harder line also. Hockney exploits the difference brilliantly in Straw on the left, Gold on the Right – straw in soft-ground, gold in hard-ground. Elsewhere he mixes drypoint and aquatint for similarly subtle visual effects. Embracing technical challenges was even then characteristic of the artist.

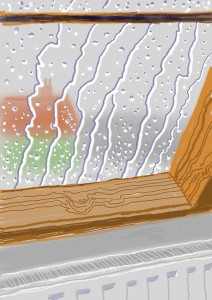

David Hockney, Rain From The Weather Series, 1973, Lithograph And Screenprint, 39″ x 30 1/2″ Edition: 98, © David Hockney / Gemini G.E.L.

His earliest print, the wonderful Self-portrait of 1954, in which he embodied his then adulation of Stanley Spencer by copying that famous eccentric’s pudding-bowl haircut, pre-bleach, was done when still in Bradford. But it was only later that he stumbled into serious printmaking almost by accident, out of economic necessity: at the Royal College of Art, at which he arrived from Bradford in 1959, materials in the print-making department were free. The same was not true in the painting department, and he had quickly run out of money. So etching it was, launching Hockney on decades of ground-breaking work in which he has obsessively investigated the potential of new techniques to dazzling effect. Even before the Grimm series, he had laid down two formidable markers, in his early Rake’s Progress, a wry look at the impact of his first visit to New York, and his illustrations to the poems of Cavafy, a set of images of homoerotic subjects whose impact derives not from their shock value, but from the tenderness and frankness with which the artist responded to the poet. At the time, showing homosexual relationships in this straightforward and touching manner was still unheard of, and Hockney’s powerful role in breaking down some of those barriers through these poetic prints was extremely important.

Over the years, a series of virtuoso prints have poured forth from this obsessively creative artist, keeping pace with his prolific painted output, including some of his most characteristic and beautiful images – for instance, the drenched Japonisme of his image of Rain from The Weather Series of 1973, in which the observed effect of a series of ripples from raindrops falling in water is enhanced visually by drips appearing to spill off the printed page.

“As technology develops at an ever more terrifying rate, and 3D printers loom on the horizon, Hockney remains one of the few artists who has responded positively to every new development”

David Hockney, Rain on the Studio Window, From My Yorkshire Deluxe Edition, 2009, Inkjet printed computer drawing on paper, 22 x 17″, An edition of 75, with 25 H.C.

To those who have followed his career with even half an eye, it can have been no surprise to find, at the recent Royal Academy blockbuster exhibition devoted to Hockney, rooms full of works produced on his iPad – what are these, exactly? Prints? Paintings? Something else? But then, Hockney has also used the humble photocopier and the fax machine to produce imagery that often defies categorisation, except that they could never be by anyone else. As technology develops at an ever more terrifying rate, and 3D printers loom on the horizon, Hockney remains one of the few artists who has responded positively to every new development, and will no doubt continue to do so – clearly the message that you’re supposed to slow down with advancing age does not apply in this case. Perhaps it is humour as much as anything that links everything he has done: this was certainly the case with his A Hollywood Collection, a series of lithographs conceived as a kind of instant art collection for a Hollywood starlet, with titles such as Picture of a Pointless Abstraction Framed under Glass.

This exhibition, curated by Richard Lloyd, reminds us that, alongside that dazzling career as Britain’s favourite painter, Hockney’s parallel achievement as a printmaker deserves equal celebration for its longevity (it’s 60 years since that first print), variety and technical brilliance, not to mention its wit and sophistication.

‘Hockney, Printmaker’ at Dulwich Picture Gallery runs from 5 February - 11 May 2014. Find out more and book online: www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk